From Classical Physics to Quantum Physics: Continuity and Rupture

Quantum physics, born at the beginning of the 20th century, did not emerge in a vacuum. It was preceded by more than two centuries of classical physics, where the laws of Newton, Faraday, and Maxwell provided a coherent framework for understanding nature. Quantum theory does not deny that legacy but transcends it, revealing the limits of those conceptions.

1. Classical Physics: Order, Causality, and Continuity

1.1 Newton and the Mechanical Universe In the 17th century, Isaac Newton (1642–1727) established the laws of motion and universal gravitation. His vision was of an ordered cosmos like a great machine: bodies obey forces that can be described with mathematical precision. Nature appeared to be a deterministic mechanism where, in principle, everything could be calculated. This paradigm offered a solid and reliable image: the universe as a clock governed by exact laws (Newton, 1687).

1.2 Faraday and the Discovery of Fields In the 19th century, Michael Faraday (1791–1867) introduced a revolutionary notion: that of a field. By studying electromagnetism, he showed that forces do not act instantaneously at a distance, as proposed by Newtonian physics, but are transmitted through an invisible field that fills space. Reality, then, was no longer a simple set of moving particles but a dynamic fabric of forces.

1.3 Maxwell and the Electromagnetic Unification Shortly after, James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879) formulated the equations of electromagnetism, showing that electricity and magnetism were manifestations of a single unified reality. Furthermore, he predicted that light was not an independent substance but an electromagnetic wave propagating in the field. With Maxwell, the universe acquired a deeper dimension: empty space was not empty but full of vibrations, waves, and invisible energies (Maxwell, 1865).

2. The Crisis of the Classical Paradigm Although powerful, the models of Newton, Faraday, and Maxwell began to show limitations towards the end of the 19th century. Phenomena such as blackbody radiation, the photoelectric effect, and the stability of the atom could not be explained by classical physics. The universe no longer fit the metaphor of the mechanical clock, nor could it be understood solely as an ocean of continuous fields. A new framework was needed, capable of explaining the infinitely small. This is where quantum physics was born.

3. The Quantum Revolution: Discontinuity and Probability

Max Planck (1900) introduced the notion of the quanta to explain blackbody radiation: energy is not continuous but discrete.

Albert Einstein (1905) explained the photoelectric effect, showing that light must be considered as a flow of particles (photons).

Niels Bohr (1913) developed an atomic model in which electrons occupy discrete orbits.

Louis de Broglie (1924) extended wave-particle duality to all matter.

Heisenberg, Schrödinger, and Born (1925–1927) formalized quantum mechanics: a universe governed by probabilities, uncertainty, and superposition.

Dirac (1928) integrated quantum theory and relativity, predicting antimatter. In contrast to the continuity of Newton, Faraday, and Maxwell, quantum theory introduced discontinuity; in contrast to classical deterministic causality, quantum theory revealed a probabilistic order.

4. Philosophy of the Transition The history of physics here shows a profound turn:

From the machine-universe (Newton) → to a universe of interpenetrating fields (Faraday and Maxwell) → to a universe of probabilities and potentialities (Bohm, Heisenberg, Schrödinger).

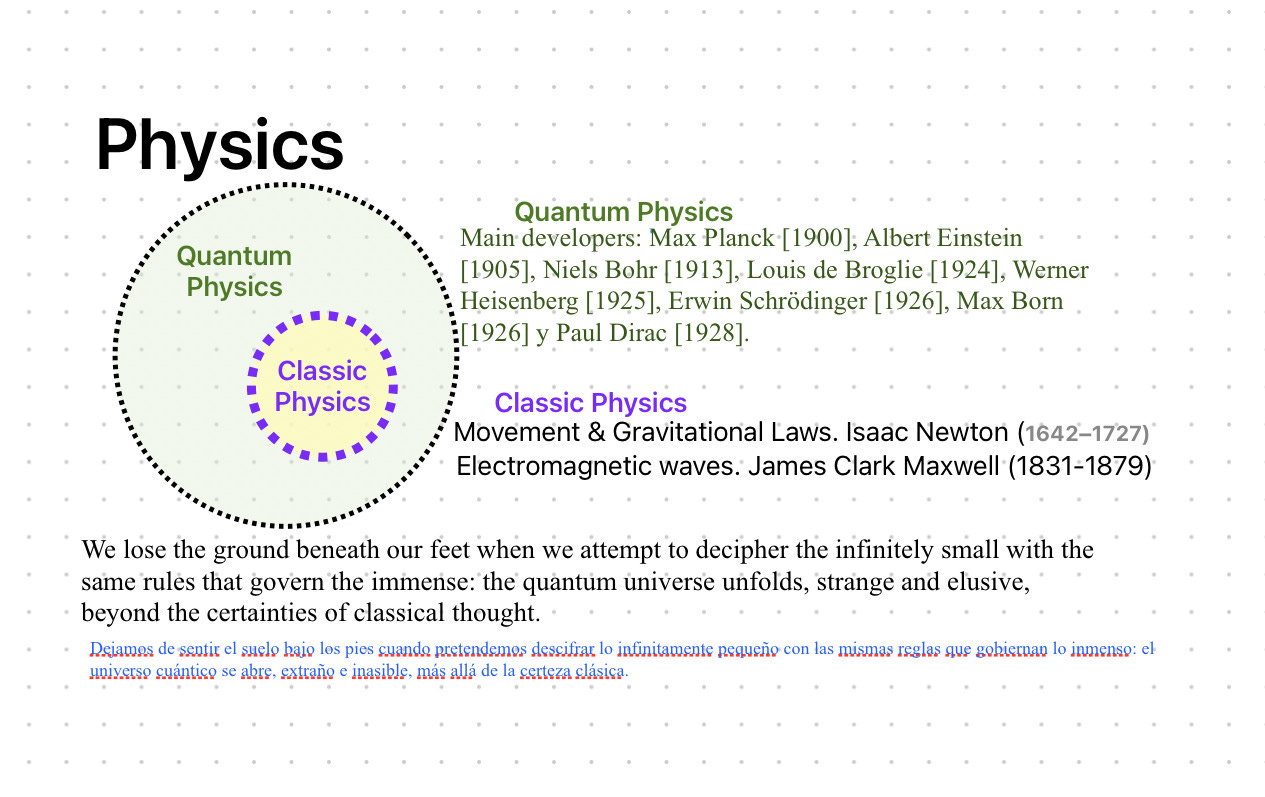

Quantum physics does not deny classical physics: it includes it as a limiting case. On large scales, we still inhabit a Newtonian-Maxwellian world; but upon descending into the microcosm, reality transforms into a discontinuous and paradoxical fabric.

Philosophically, this transition reveals that our knowledge is not absolute but historical and perspectival: each scientific theory is a way of organizing the real, and each paradigm opens and closes horizons of understanding (Kuhn, 1962).

Synthesis Classical physics—with Newton, Faraday, and Maxwell—offered us a solid, continuous, and causal universe. Quantum physics—with Planck, Einstein, Bohr, de Broglie, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, Born, and Dirac—revealed to us a discontinuous, probabilistic, and mysterious cosmos. These two visions do not exclude each other but complement each other: the first describes the everyday world of the macroscopic, the second illuminates the enigma of the microscopic. From this tension between continuity and discontinuity, between determinism and probability, perhaps the greatest philosophical lesson emerges: reality is broader and deeper than any conceptual framework. Science, far from offering absolute certainties, invites us to inhabit a mystery in perpetual unfolding.

The Discoverers and Founders of Quantum Physics

Quantum physics was not the fruit of an isolated discovery or a single individual genius but the result of a radical transformation in the way reality is conceived. Its birth at the beginning of the 20th century marked one of the most profound intellectual revolutions in the history of science: the shift from a classical vision of the universe—ordered, continuous, and deterministic—to a quantum vision, in which the real appears as discontinuous, probabilistic, and fundamentally interconnected.

1. The Origin of the "Quantum": Planck and Einstein In 1900, Max Planck introduced, almost reluctantly, the notion of the quantum of action. While studying blackbody radiation, he discovered that energy could not be emitted continuously but in discrete packets (quanta). This act of rupture opened an unexpected horizon: nature did not always obey the mathematical continuity of classical physics but a logic of jumps and discontinuities. Planck, without entirely intending to, became the founder of quantum theory. A few years later, in 1905, Albert Einstein took a decisive step by explaining the photoelectric effect: light itself had to be considered as a flow of particles—photons—and not only as a wave. Einstein thus introduced a radical duality in the understanding of reality: matter and energy could behave in contradictory ways depending on the context of observation. This discovery earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 and consolidated the ground for the quantum revolution.

2. The Structure of the Atom: Bohr and de Broglie In 1913, Niels Bohr proposed his atomic model: electrons do not revolve around the nucleus in arbitrary orbits but in discrete trajectories. Each transition of an electron between these orbits involves the emission or absorption of a quantum of energy. Bohr not only introduced an innovative mathematical model but also a philosophical intuition: atomic reality had to be understood from a new conceptual framework, beyond classical common sense. Subsequently, in 1924, Louis de Broglie formulated his famous hypothesis of wave-particle duality. If light could be both wave and particle, why not matter as well? De Broglie argued that every material particle possesses an associated wavelength, initiating a profoundly holistic conception of the universe: the solid and tangible revealed itself as oscillation, vibration, pattern.

3. The Formulation of Quantum Mechanics The period between 1925 and 1927 marked the formal birth of quantum mechanics.

Werner Heisenberg (1925) created matrix mechanics, where physical quantities are described as abstract algebraic relations and not as concrete trajectories.

Erwin Schrödinger (1926) developed the wave equation, offering a more intuitive representation of quantum systems as wave functions that evolve over time.

Max Born (1926) gave a decisive interpretive turn: the wave function does not describe a physical reality in itself but the probability of an event occurring. With Born, physics ceased to be strictly deterministic: the real became a field of potentialities.

In 1927, Heisenberg formulated his uncertainty principle, showing that it is not possible to know simultaneously with precision certain pairs of variables, such as the position and momentum of a particle. Uncertainty ceased to be a technical limitation and became an ontological feature of reality: the universe, at its most intimate level, is indeterminate.

4. The Relativistic Synthesis: Dirac Finally, in 1928, Paul Dirac united quantum mechanics with special relativity, creating an equation that predicted the existence of antimatter: the positron. With Dirac, quantum theory showed its capacity not only to describe but also to reveal unsuspected realities that would later be confirmed experimentally.

5. A Scientific and Philosophical Revolution Quantum physics is not just a scientific theory: it is a paradigm shift in the way we think about reality. While the classical physics of Newton and Laplace conceived of a mechanistic universe governed by exact and predictable laws, quantum physics confronts us with a cosmos where certainty is replaced by probability, where matter is both particle and wave, and where the observer participates in the constitution of the phenomenon. This transition has been compared to an ontological leap: from a solid and deterministic world to a relational, interdependent, and mysterious universe. Philosophers of science like Thomas Kuhn and Karl Popper recognized in quantum theory a paradigmatic example of how science not only accumulates data but radically transforms the categories with which we understand the real.

✅ In summary: the founders of quantum physics—Planck, Einstein, Bohr, de Broglie, Heisenberg, Schrödinger, Born, and Dirac—not only gave birth to a new physical theory but also forced us to rethink the notions of causality, objectivity, and reality. Quantum theory is not only a physics of the microscopic: it is also a philosophy of uncertainty, a mirror in which humanity discovers that the universe is not a predictable machine but a living mystery that reveals itself in probabilities.

Your point is very valuable, and it reflects one of the most widespread interpretations: consciousness as an emergent property of cognitive complexity. However, there is another line of reflection that is also worth considering. Perhaps consciousness is not merely a byproduct of complex physical processes, but rather a fundamental property of nature itself, comparable to electromagnetism, gravity, or the nuclear forces. From this perspective, consciousness would be a structural principle of the universe that manifests and organizes itself in biological systems, rather than a simple epiphenomenon of them. The deeper question, then, is not only how consciousness arises from matter, but whether matter itself is already inscribed within a field of consciousness that permeates and makes it possible.

Tu planteamiento es muy valioso, y refleja una de las interpretaciones más extendidas: la conciencia como una propiedad emergente de la complejidad cognitiva. Sin embargo, hay otra vía de reflexión que también merece ser considerada. Tal vez la conciencia no sea únicamente un producto derivado de procesos físicos complejos, sino una propiedad fundamental de la naturaleza misma, comparable al electromagnetismo, la gravedad o las fuerzas nucleares. Desde esta perspectiva, la conciencia sería un principio estructural del universo que se manifiesta y organiza en los sistemas biológicos, en lugar de un simple epifenómeno de ellos. La cuestión de fondo, entonces, no es solo cómo surge la conciencia a partir de la materia, sino si la materia misma está ya inscrita en un campo de conciencia que la atraviesa y la posibilita.