Knowledge, Experience, Emotions. Part IV

Integrating Unpleasant Emotions: A Comparative Dialogue Between Buddhism, Christian Mysticism, and Sufism

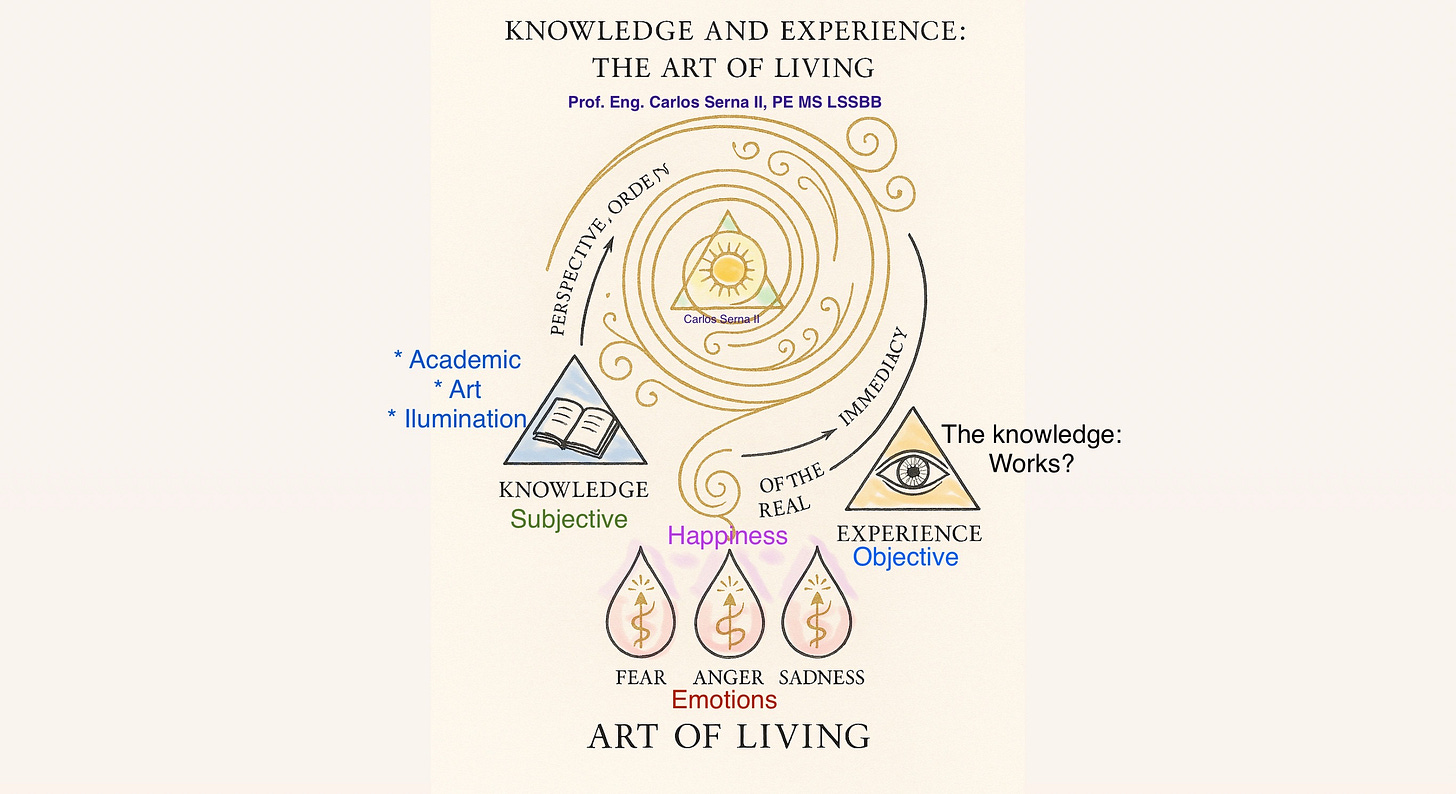

Framework How can unpleasant emotions—fear, anger, sadness, shame—be transformed into practical wisdom? Three major traditions offer convergent protocols: (i) recognizing the emotion without identifying with it, (ii) purifying it through attentional or ascetic discipline, and (iii) transmuting it into compassion, charity, or love. Although their languages and ontologies differ, all three paths describe an arc of integration that avoids both repression and overwhelm.

Buddhism: See, Release, Compassionate In Buddhism—Theravāda and Mahāyāna—afflictive emotions (kleshas) are understood as conditioned patterns that cloud the mind’s clarity. Practice revolves around two axes:

Mindfulness (sati / smṛti): observing sensations, feelings, and thoughts “as they are,” without judgment or ego-centered fusion.[^1]

Insight (prajñā): seeing the conditioned co-arising (pratītya-samutpāda) and emptiness (śūnyatā) of affective phenomena: emotions lack fixed essence and change when understood.[^2]

Anger, for example, is contemplated as a transient phenomenon. Its bodily “heat,” its narratives, its impulse to react are seen and let go. As attachment (upādāna) and aversion (dveṣa) diminish, compassion (karuṇā) emerges as a non-violent response.[^3] Zen radicalizes this pedagogy with koans that deactivate conceptual fixation: no “emotional truth” should be absolutized.[^4]

Buddhist key: Detached contemplation → insight into impermanence/interdependence → operative compassion.

Christian Mysticism: Purification, Illumination, Union In the Christian tradition, “unpleasant” emotions can be read as passions that, without grace or discernment, disorder love. The classical path: purification – illumination – union.

Purification: asceticism and examination of the heart (Evagrius, Cassian). “Acedia,” anger, or sadness are named, confessed, and offered in prayer; discipline (fasting, vigils, silence) reorders desire.[^5]

Illumination: Affective intelligence quiets to listen to God’s will; suffering becomes an occasion for humility and charity (Teresa of Ávila, Ignatius of Loyola).[^6]

Union: The “dark night” (John of the Cross) is the most radical pedagogy: God purifies affections and images; affective loss is transmuted into theological charity. Emotion is not denied: it is elevated and oriented toward the Good.[^7]

Christian key: Discernment and offering → charity → transfiguration of affect into love of neighbor.

Sufism: From Nafs to the Expansion of the Heart Sufism understands the affective journey as a refinement of the nafs (psycho-passional self) toward the qalb (heart) and ruh (spirit). The alchemy of the heart relies on:

Dhikr (remembrance of God): repetition of divine Names that pacifies emotional agitation and anchors attention in Presence.[^8]

Sohbet / adab (companionship and rectitude): the bond with a master and relational ethics “polish” reactivity (anger, jealousy, envy) into courtesy and service.

Sabr / rida (patience and contentment): unpleasant emotions are reinterpreted as occasions for tawakkul (trust): “The wound is the place where the light enters.” (attributed to Rūmī).[^9]

The movement is from contraction (qabd) to expansion (bast): emotion narrows the self; remembrance of God expands it and makes it hospitable.

Sufi key: Remembrance and polishing of the heart → trust → loving service.

Convergences and Differences Structural Convergences

No repression: observe and name the emotion (mindfulness; examination; dhikr).

No identification: dissolve the factual self (anattā / kenosis / polishing of the nafs).

Transmutation: compassion (Buddhism), charity (Christianity), mercy/service (Sufism).

Practice: sustained attentional/ascetic discipline; community/master; continuous examination.

Differences in Horizon

Ontology: emptiness and interdependence (Buddhism) vs. personal God and grace (Christianity) vs. divine oneness (tawḥīd) and theopathy (Sufism).

Affective language: universal impersonal compassion (karuṇā) vs. Christian agape (theological love) vs. divine erotic-mystical love (maḥabba / ʿishq).

Teleology: liberation from suffering (nirvāṇa), deification by grace (theōsis), or annihilation in God (fanā’) with subsistence in Him (baqā’).

An Integrative Framework: From Map to Affective Territory The three traditions can be reread as phases of the same “affective hermeneutic circle”:

Mapping (knowledge): doctrine of affect (kleshas/virtues; passions/virtues; states of the nafs/maqāmāt).

Verification (experience): situated practice (meditation, sacraments/prayer, dhikr/service).

Adjustment (emotion as signal): unpleasant emotion indicates a mismatch between map and territory; it is reworked into compassion-charity-service.

Stabilization (embodied wisdom): transformed habits (pāramitās; theological virtues; adab/sabr).

Thus, “negative” emotion ceases to be residue to be eliminated and becomes an indicator and fuel for practical wisdom.

Operational Epilogue: Comparative Micro-Protocol

Buddhist: 1) notice (breath), 2) name (“anger, anger”), 3) inquire into its dependent cause, 4) release, 5) cultivate mettā.

Christian: 1) Ignatian examen (dominant affect), 2) discern spirits (consolation/desolation), 3) offer in prayer, 4) concrete act of charity.

Sufi: 1) gentle dhikr (Name), 2) remember adab (courtesy), 3) practice sabr in contraction, 4) serve others (bast).

Notas

[^1]: Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (MN 10). Véase Bhikkhu Anālayo, Satipaṭṭhāna: The Direct Path to Realization (Birmingham: Windhorse, 2003).

[^2]: Nāgārjuna, Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, cap. 24; traducción de Tola & Dragonetti (Madrid: Trotta, 1997).

[^3]: Śāntideva, Bodhicaryāvatāra, cap. 6 (paciencia/compasión). Ed. Crosby & Skilton (Oxford: OUP, 1996).

[^4]: Mumonkan (El paso sin puerta), kôan 33. Ed. Shibayama (Boston: Shambhala, 1974).

[^5]: Evagrio Póntico, Tratado práctico; Juan Casiano, Conlationes. Ed. monástica (BAC).

[^6]: Teresa de Jesús, Libro de la vida; Ignacio de Loyola, Ejercicios espirituales, n. 313-336 (discernimiento).

[^7]: Juan de la Cruz, Noche oscura, en BAC; cf. Denys Turner, The Darkness of God(Cambridge: CUP, 1995).

[^8]: Al-Ghazālī, Iḥyā’ ‘Ulūm al-Dīn (Libro del Recuerdo); A. Schimmel, Mystical Dimensions of Islam (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1975).

[^9]: Rūmī, Mathnawī, I: 1129-1135; Annemarie Schimmel, Rumi’s World (Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1994).

Bibliografía selecta

• Anālayo, Bhikkhu. Satipaṭṭhāna: The Direct Path to Realization. Windhorse, 2003.

• Davidson, Richard J. The Emotional Life of Your Brain. Hudson Street, 2012.

• Denys Turner. The Darkness of God. Cambridge UP, 1995.

• Evagrius Ponticus. Praktikos & Chapters on Prayer. Cistercian, 1972.

• Ignatius of Loyola. Ejercicios espirituales.

• Nāgārjuna. Mūlamadhyamakakārikā. Trotta, 1997.

• Rūmī. Mathnawī.

• Śāntideva. Bodhicaryāvatāra. OUP, 1996.

• Teresa de Jesús. Libro de la vida; Moradas.

• Schimmel, Annemarie. Mystical Dimensions of Islam. UNC Press, 1975.