Knowledge, Experience, Emotions. Part II

The Philosophical Status of the “Unpleasant”

1.1. Aristotle and the Golden Mean For Aristotle, virtue consists of inhabiting the golden mean between extremes of excess and deficiency¹. Fear, for example, is not bad in itself, but becomes so when it turns into cowardice or recklessness. Thus, unpleasant emotions are not to be eliminated but must find their proper place in ethical life.

1.2. Stoicism: Mastering Disturbance In Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, by contrast, passions are seen as disturbances of the soul that must be tamed through reason and philosophy². Here emerges the idea of inner self-governance: we cannot prevent something from affecting us, but we can decide how to respond.

1.3. Phenomenology: The Appearance of Emotion Husserl and Merleau-Ponty remind us that emotion is not an accidental addition but a fundamental way in which the world appears to us³. Fear is not merely a biological state but a mode in which the world reveals itself as threatening. The unpleasant, therefore, is revelation, not mere annoyance.

Contemporary Psychology and Neuroscience 2.1. Adaptive Function Paul Ekman identified six universal basic emotions: joy, sadness, fear, anger, disgust, and surprise⁴. Four of these are typically considered “unpleasant,” yet they serve adaptive functions: anger signals injustice, sadness processes loss, fear prevents risk, and disgust avoids harm.

2.2. Emotional Regulation Richard Davidson demonstrated that the prefrontal cortex mediates the regulation of emotional responses originating in the limbic system⁵. This means that “knowledge” (reason) and “experience” (emotion) engage in dialogue within the brain itself.

2.3. Emotional Plasticity Contemporary neuroscience shows that practice—whether meditation, writing, or therapy—alters neural connections. Experience transforms knowledge, and vice versa, confirming the thesis of this dual dynamic.

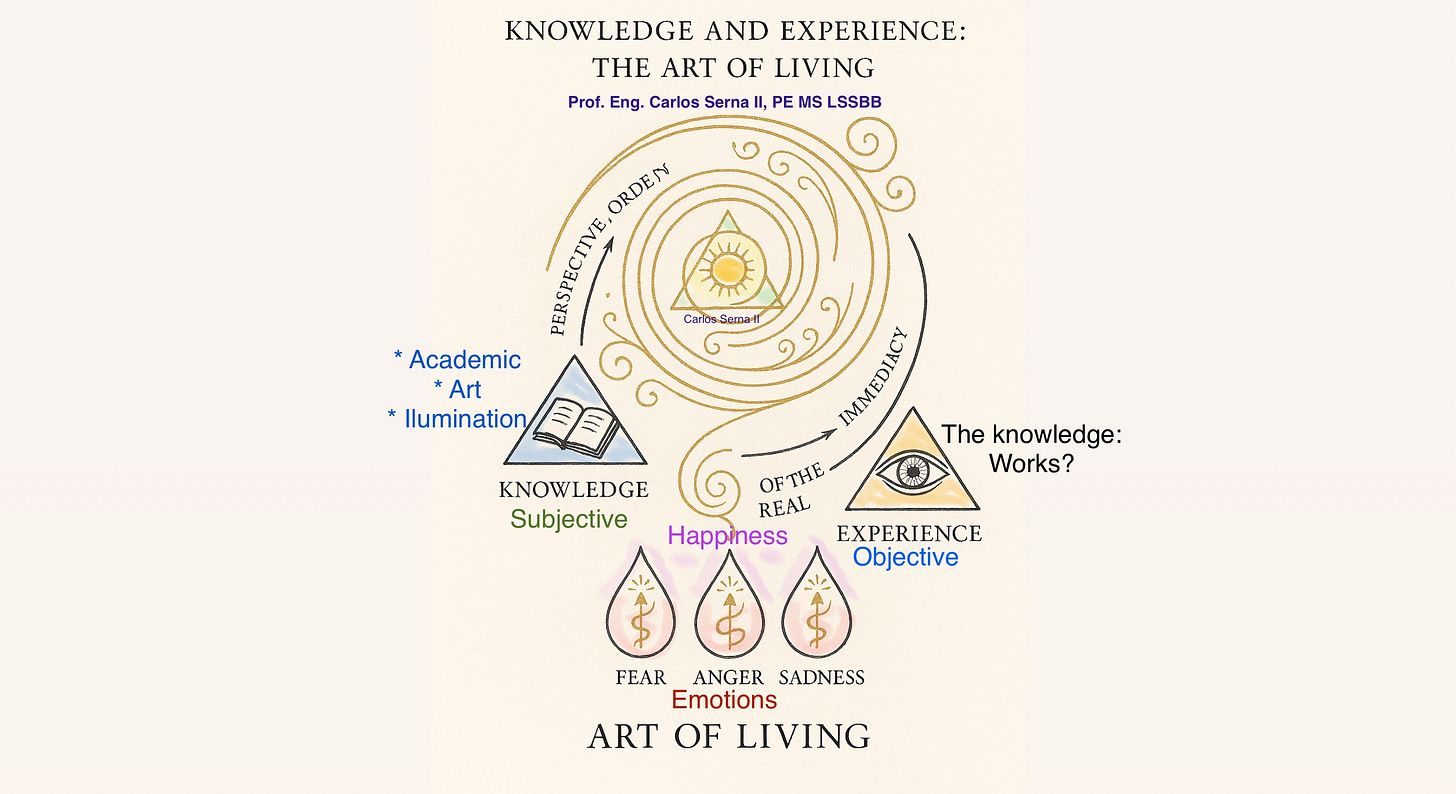

Three Pathways of Knowledge and Their Emotional Application 3.1. The Scientific-Academic Pathway Science provides theories, statistics, and explanations that help contextualize unpleasant emotions. Knowing that anxiety is a common physiological reaction can reduce its demonization.

3.2. The Artistic-Cultural Pathway Art transforms pain into symbol. Greek tragedy, Rilke’s poems, or Munch’s paintings show us that the unpleasant can be sublimated into shared beauty.

3.3. The Spiritual or Mystical Pathway In traditions such as Sufism, unpleasant emotions are tests that reveal the state of the soul. Rumi writes: “The wound is the place where the light enters you”⁶. Here, negative emotions are reinterpreted as a path to the transcendent.

Dialogue Between Traditions 4.1. Mystical Christianity The “dark night” of St. John of the Cross is the archetype of unpleasant emotion as purification⁷. Suffering is not mere misfortune but a passage toward union with the divine.

4.2. Buddhism The kleshas (afflictions) are illusions to be observed without attachment. The practice of mindfulness teaches us to embrace anger and sadness as one would embrace a crying child⁸.

4.3. Neuroscience Current research on meditation confirms that observing emotions without identifying with them reduces their impact and strengthens resilience⁵. Science and spirituality converge.

Openness and Diversity as Emotional Training Cultivating equanimity requires openness to new experiences. Traveling, learning, and engaging with other cultures expand the horizon of the self. Gadamer calls this the “fusion of horizons”⁹. Thus, every unpleasant emotion is contextualized within a broader framework.

Historical Examples

Nelson Mandela, who transformed bitterness into a political vision of reconciliation while in prison.

Frida Kahlo, who turned physical pain into canvas and cultural myth.

Albert Einstein, whose discomfort with the gaps in classical physics led him to formulate the theory of relativity. In all cases, the unpleasant was the seed of transformation.

Practical Epilogue: Integration Exercises

Phenomenological Journal: Write down an unpleasant emotion and describe it without judgment. How does it manifest in the body? What does it reveal about the world?

Reality Check: Ask with each emotion: Does what I feel correspond to reality or to a projection?

Artistic Transmutation: Write, paint, or dance based on the unpleasant emotion.

Contemplative Practice: Spend 10 minutes daily observing emotions without identifying with them.

Cultural Openness: Expose yourself to new experiences (a language, a book, a landscape) that relativize the boundaries of the self.

Conclusion Unpleasant emotions are neither flaws of the organism nor punishments of fate: they are hidden teachers. They remind us of our vulnerability and, at the same time, our capacity for transformation. The path to their integration lies in the alchemy between knowledge and experience, which unfolds along three complementary pathways: the scientific, the artistic, and the spiritual.

From this alchemy emerges a practical truth: the unpleasant cannot be avoided, but it can be transmuted into wisdom, creativity, and compassion. Those who master this art will attain a deeper form of happiness: not a fleeting joy, but the equanimous tranquility of one who has learned to embrace all of life, even its shadows.