Neuroalgorithm: Between Neuroscience, Philosophy, and Expanded States of Consciousness

Jacobo Grinberg-Zylberbaum

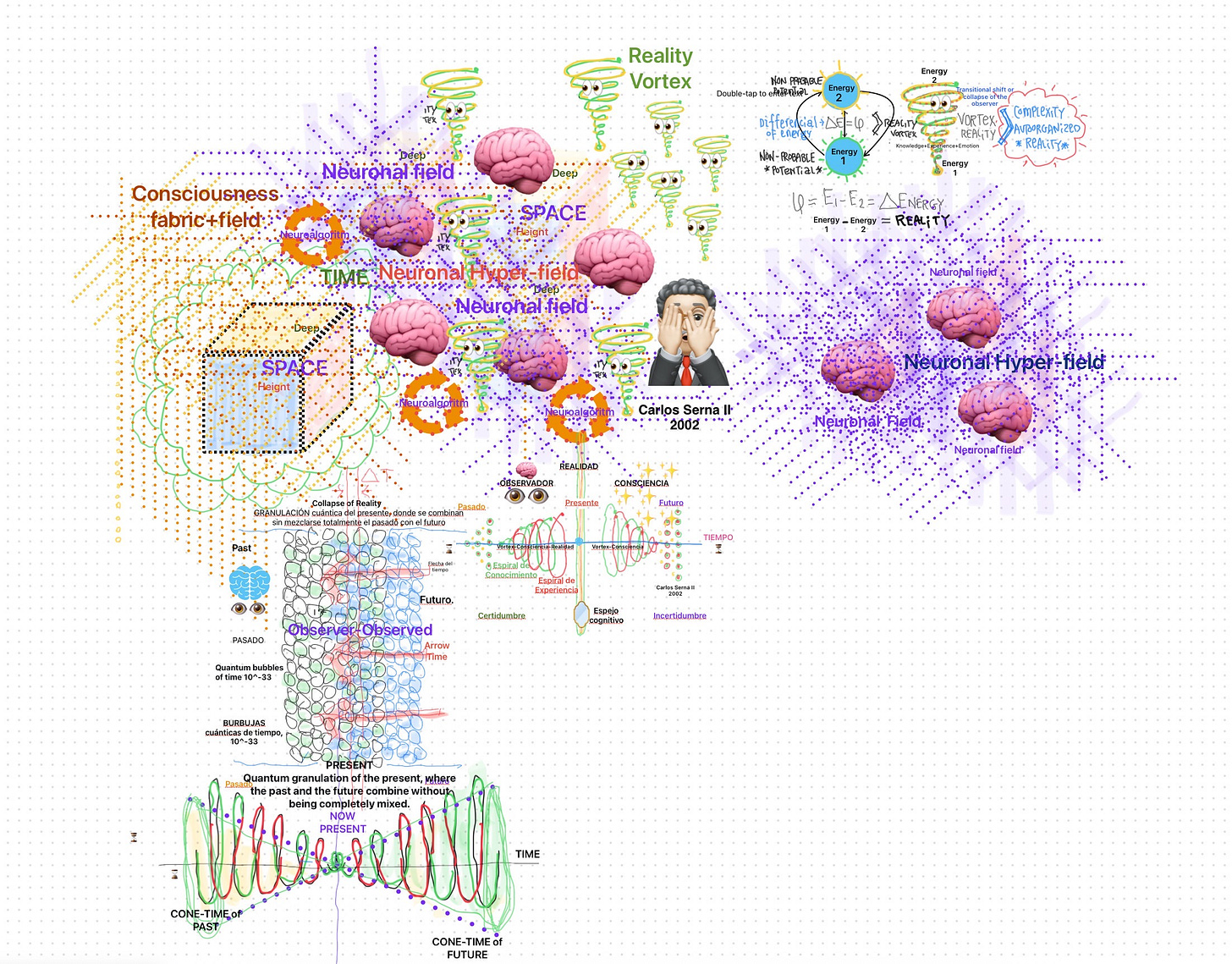

In a simple and accessible way, I explore the concept of the neuroalgorithm developed by Jacobo Grinberg-Zylberbaum as an explanatory model of conscious perception. I examine its relationship with contemporary neuroscience, philosophical phenomenology, and shamanic practices. I also connect this concept with current theories on brain dynamics, predictive construction of the world, and expanded states of consciousness.

1. Introduction

Although the problem of consciousness remains one of the most persistent challenges in science and philosophy (Chalmers, 1995; Koch, 2004), here I seek to offer a simplified and approachable definition. Among the many theories I have studied, the one that convinces me most, both scientifically and philosophically, is Jacobo Grinberg-Zylberbaum’s proposal. Emerging from unconventional contexts, Grinberg’s Sintergic Theory (1991) holds a singular place. At its center lies the concept of the neuroalgorithm, understood as the set of neural processes that make possible the translation of fundamental reality into perceptual experience.

This article examines that concept in dialogue with contemporary theories such as the Free Energy Principle (Friston, 2010), neuronal synchronization (Varela et al., 2001), and the phenomenological ontology of perception (Merleau-Ponty, 1945).

2. The Neuroalgorithm in Grinberg-Zylberbaum’s Work

Grinberg defines the neuroalgorithm as the organizing function of brain activity that enables the construction of conscious experience. According to him, the lattice of space—a network of pre-perceptual informational potentials—is not directly accessible, but only through the algorithmic decoding performed by neuronal activity (Grinberg, 1991).

This approach implies that perception does not reflect reality as it is, but rather constitutes an interpretive translation that emerges from the fundamental field of information known as the lattice. Consequently, the observer is never independent from the observed, anticipating phenomenological critiques of the positivist paradigm in science (Husserl, 1931; Merleau-Ponty, 1945).

3. Neuroalgorithm and Neuronal Coherence

A central aspect of Grinberg’s proposal is the importance of neuronal coherence. Contemporary neuroscience has confirmed that oscillatory synchronization (especially in gamma frequencies) plays a critical role in perceptual unification (Singer, 1999; Varela et al., 2001).

Grinberg-Zylberbaum suggested that a brain with higher coherence produces a more stable and complex field, capable of generating deeper and more unified perceptions (high sintergy). In mystical or shamanic states, this increase in coherence would allow access to subtle levels of reality, expanding the range of the neuroalgorithm beyond the ordinary (Grinberg, 1991).

4. Neuroalgorithm and Expanded States of Consciousness

Grinberg-Zylberbaum documented phenomena observed in shamanic and meditative practices, including his well-known collaboration with the healer Pachita (Grinberg, 1994). There, he observed that the neuroalgorithm reconstructs itself, becomes self-referential, and reorganizes in order to integrate patterns of information inaccessible in ordinary states.

In this sense, the neuroalgorithm is not rigid but plastic: it can be transformed through contemplative practices, shamanic rituals, or techniques for expanding consciousness. This resonates with William James’ (1902) reflections on the variety of religious experience and with Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious (1959), understood as a transpersonal field of images and meanings.

5. Bridges with Contemporary Neuroscience

Grinberg’s vision can be placed in dialogue with several modern frameworks:

• Free Energy Principle (Friston, 2010): the brain as a predictive machine that minimizes surprise through internal models, resembling the neuroalgorithm’s role as an active translator of reality.

• Integrated Information Theories (Tononi, 2008): consciousness as integration of information, resonating with the idea of neuronal coherence as the perceptual basis.

• Quantum Holism (Bohm, 1980): Bohm’s implicate order, where reality unfolds from a unified field, recalls Grinberg’s lattice.

6. Philosophical Implications

The neuroalgorithm raises significant epistemological and ontological consequences:

1. Epistemological: science never observes reality in itself but only what the neuroalgorithm constructs (echoing Kant and modern constructivism).

2. Ontological: consciousness does not reside solely in the brain but in the interaction between the fundamental field and the neuronal algorithm.

3. Phenomenological: what appears as “world” is always the correlate of conscious intentionality (Merleau-Ponty, 1945).

7. Conclusion

Although formulated outside the academic mainstream, Grinberg’s neuroalgorithm anticipates contemporary debates on the construction of reality, brain dynamics, and the nature of consciousness. Its value lies in offering an integrative model linking neuroscience, phenomenology, and spirituality, opening a horizon for studying consciousness as an interface between the physical and the experiential.

Referencias

• Bohm, D. (1980). Wholeness and the Implicate Order. Routledge.

• Chalmers, D. (1995). Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2(3), 200–219.

• Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11, 127–138.

• Grinberg-Zylberbaum, J. (1991). La teoría sintérgica. Pax.

• Grinberg-Zylberbaum, J. (1994). Psicofisiología del chamanismo. Pax.

• Husserl, E. (1931). Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. Allen & Unwin.

• James, W. (1902). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Longmans.

• Jung, C. G. (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton University Press.

• Koch, C. (2004). The Quest for Consciousness. Roberts & Co.

• Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phénoménologie de la perception. Gallimard.

• Singer, W. (1999). Neuronal synchrony: a versatile code for the definition of relations? Neuron, 24, 49–65.

• Tononi, G. (2008). Consciousness as integrated information: a provisional manifesto. The Biological Bulletin, 215(3), 216–242.

• Varela, F. J., Lachaux, J. P., Rodriguez, E., & Martinerie, J. (2001). The brainweb: phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2, 229–239.