Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Español English

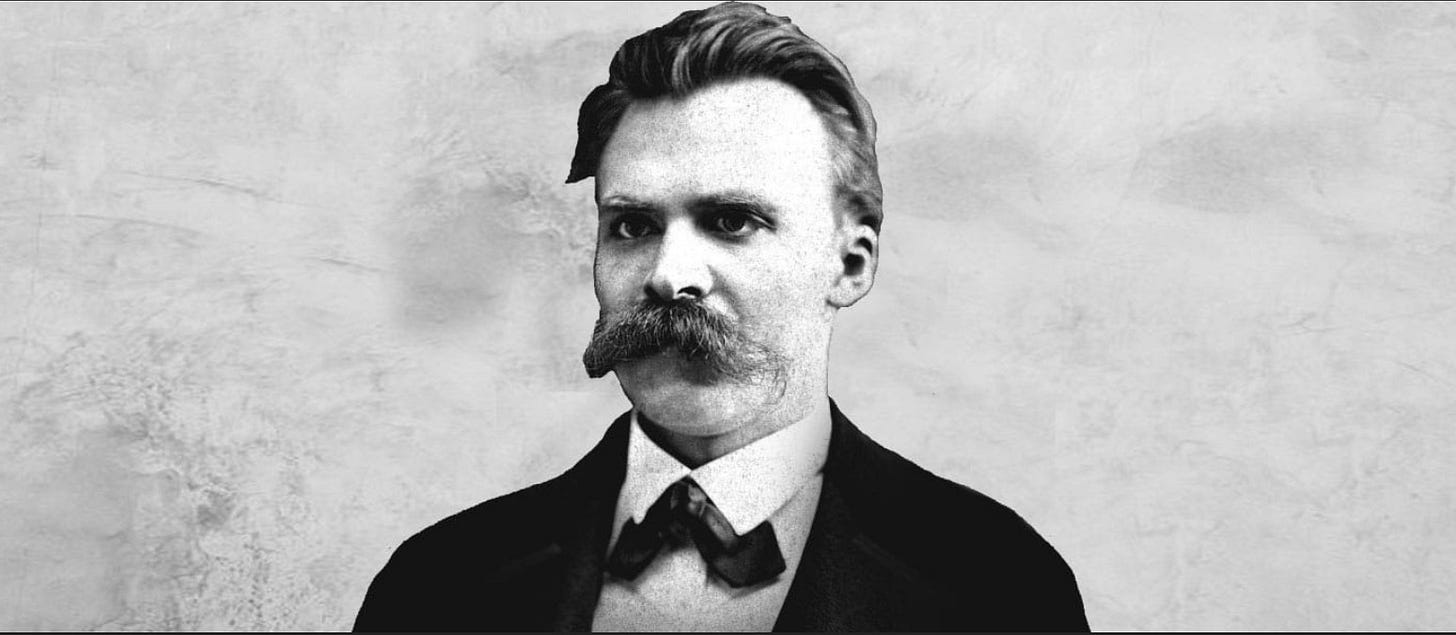

Analysis of the Prologue to “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” by Friedrich Nietzsche

Author: Prof. Eng. Carlos Serna II, PE MS LSSBB

Introduction

The Prologue to Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883), written by Friedrich Nietzsche, is a foundational text within Nietzschean philosophy. It condenses many of the central ideas of his work through poetic, symbolic, and philosophical expression. Functioning as a threshold to the book’s aphoristic and narrative corpus, the Prologue not only introduces the character of Zarathustra—a symbolic figure inspired by the Persian prophet Zoroaster—but also sets forth a radical critique of Western culture, a genealogy of the human spirit, and a proposal for moral revaluation culminating in the notion of the Übermensch (superhuman or overhuman).

This analysis examines the Prologue through a rigorous philosophical lens, exploring its ontological, anthropological, moral, and metaphysical dimensions, while situating it within the broader framework of modern and post-metaphysical thought.

1. Withdrawal and Return: The Archetypal Structure of the Sage’s Path. Zarathustra descends from the mountain after ten years of solitude—an act that symbolically configures the sage’s ascetic retreat, followed by the decision to share the wisdom attained. This structure recalls the figure of Plato’s philosopher-king or the biblical prophet, yet Nietzsche subverts its content. Zarathustra does not descend bearing eternal truths but rather a fiery critique of established values, proclaiming the death of God and the necessity of a new horizon of meaning.

This cycle of retreat and return expresses a core tension between creative solitude and transformative communication. Zarathustra is, like Nietzsche himself, a tragic spirit who has broken with herd morality and seeks to create new values from the experience of overcome nihilism.

2. The Death of God and the Twilight of Absolute Values. One of the most famous passages in the Prologue proclaims, “God is dead.” Though this idea was already articulated in The Gay Science, in Zarathustra it appears not as a rational statement, but as a mythical-existential event. It is not merely a denial of a supreme being, but a declaration of the collapse of the entire metaphysical structure that upheld Western transcendent values: absolute truth, universal morality, the immortal soul, providential history.

The death of God entails a crisis of meaning that inaugurates nihilism. However, Nietzsche does not stop at this diagnosis—he demands that nihilism be overcome through the active creation of new values, values no longer reliant on an external foundation but grounded in the affirmation of life itself.

3. The Übermensch as Posthuman Ideal and Figure of Becoming. The idea of the Übermensch appears in the Prologue as an affirmative response to nihilism. Humanity, Zarathustra tells us, is “a rope stretched between the animal and the overhuman”—a bridge, not a goal. This anthropological vision redefines the human being not as a fixed essence nor as a self-sufficient rational subject (as in Descartes or Kant), but as a passage, a creative becoming, an open possibility.

The Übermensch should not be interpreted as a biologically superior being, but as a symbolic figure of one who has transcended traditional morality—particularly Christian morality rooted in resentment—and affirms life in all its dimensions, including its pain, chaos, and flux. In this sense, the Übermensch is a “new legislator,” a poet of values unafraid of the abyss of meaninglessness, having learned to dance above it.

4. Contempt for the “Last Man”: A Critique of Modernity and Bourgeois Hedonism. A central figure in the Prologue is the “last man,” symbol of modern spiritual decay. This contented, comfortable man, devoid of passion or higher aspirations, embodies Nietzsche’s notion of the negation of elevated life. He lives without risk, depth, or will to power. He rejects suffering, but also greatness.

The “last man” represents the culmination of a process of leveling, domestication, and mediocrity driven by liberal modernity and Judeo-Christian morality. Instead of the tragic hero or the Dionysian creator, the modern world produces anesthetized individuals who seek comfort and fear difference. Nietzsche’s critique here anticipates, in spirit, the later diagnoses of Heidegger’s technological society, Ortega y Gasset’s mass culture, and Marcuse’s one-dimensional man.

5. The Symbol of the Sun: The Will to Give and Dionysian Affirmation. The sun is the central symbol in Zarathustra’s discourse. Its light does not dominate or impose—it gives. Like the sage, the sun rises to radiate, not out of necessity but from overabundance. This symbol encapsulates the core of Nietzsche’s affirmative ethics: the supreme value is not duty, sacrifice, or redemption, but the vital overflow of the one who gives without expectation, who creates without asking permission.

In this image, Nietzsche reclaims the Dionysian as an ontological key: the world is creation, becoming, excess. The true sage is not one who escapes the world in search of another reality (as in Platonism or Christianity), but one who says “yes” to the changing flow of existence, to laughter, pain, and chance.

Conclusion

The Prologue to Thus Spoke Zarathustra is a philosophical-poetic manifesto that inaugurates a new way of thinking—not as a closed system, but as an aesthetic, transformative, and performative experience. In its dramatic and symbolic structure are condensed Nietzsche’s most radical intuitions: the death of God, the critique of nihilism, the will to power, the need to create new values, and the figure of the Übermensch as the horizon of a humanity yet to come.

Far from offering certainties, the Prologue invites an inner and collective journey in which philosophy is no longer contemplation, but transformation. In Zarathustra, Nietzsche is not transmitting a doctrine, but provoking a tremor—a metamorphosis of the soul that urges us to become more than we are.

Academic References

• Nietzsche, F. (2003). Thus Spoke Zarathustra (trans. A. Sánchez Pascual). Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

• Heidegger, M. (1991). Nietzsche (Vol. I & II). Madrid: Trotta.

• Deleuze, G. (1962). Nietzsche and Philosophy. Paris: PUF.

• Löwith, K. (1997). From Hegel to Nietzsche: The Revolutionary Break in 19th Century Thought. Madrid: Katz.

• Safranski, R. (2003). Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography. Barcelona: Tusquets.

• Bataille, G. (1994). The Guilty One. Barcelona: Anagrama.

✦ Philological and Comparative Analysis of the Prologue to Thus Spoke Zarathustra

▸ §1 – Zarathustra’s Departure: The Archetype of the Solar Sage

Original (German): „Als Zarathustra dreißig Jahre alt war, verließ er seine Heimat und den See seiner Heimat und ging in das Gebirge.“

Translation: “When Zarathustra was thirty years old, he left his homeland and the lake of his homeland and went into the mountains.”

Philological Analysis:

• verließ (“left”): a strong verb implying a radical break—not merely geographic but spiritual. It suggests Nietzschean renunciation of “homeland” as cultural, moral, and linguistic tradition.

• das Gebirge: not just “the mountain,” but “the mountain range” or “the mountainous realm”—a recurring symbol of spiritual elevation and philosophical solitude.

Comparisons:

• Plato: The ascent to the intelligible world in the Allegory of the Cave (Republic, Book VII) shares the image of elevation, but Nietzsche inverts the vector—Zarathustra does not ascend to escape the sensible world, but descends to transform it.

• Gospels: Jesus also retreats to the desert or mountain before beginning his public mission. In both cases, solitude precedes revelation.

• Eastern Mysticism: Comparable to the rishis retreating to the Vedic forests or the Taoist hermit returning when wisdom no longer requires speech.

▸ §2 – Inner Maturation: “I love those who…”

Text: „Zarathustra ward müde der Einsamkeit…“

Translation: “Zarathustra grew weary of solitude…”

Philological Analysis:

• ward müde (“grew weary”): not simple fatigue, but spiritual maturation. The verb werden marks ontological transformation. Zarathustra becomes one who must give.

• die Sonne hatte ihn gelehrt: “the sun had taught him”—a potent metaphor: light as wisdom that does not accumulate but radiates.

Comparisons:

• Heraclitus: the logos as fire that spreads, not fixed doctrine.

• Gospel of John: “The true light, which gives light to everyone, was coming into the world” (John 1:9), here reinterpreted as vital affirmation, not redemptive grace.

• Bhagavad Gītā: Krishna teaches the sage to act without attachment, as offering (karma yoga).

▸ §3 – The Announcement of the Übermensch

Text: „Ich lehre euch den Übermenschen.“

Translation: “I teach you the overman.”

Philological Analysis:

• Übermensch: literally “the one beyond human,” not “superior man.” The prefix über- denotes transcendence, but also inner overcoming (Selbstüberwindung).

• Ich lehre euch: formula of prophetic authority, yet distorted—not Moses with the tablets, but a new prophet without God.

Comparisons:

• Heidegger: argues that the Übermensch still operates within Western metaphysics, as an inversion of values, and thus prefers a focus on Being.

• Gautama Buddha: the arhat also transcends human conditioning—but Zarathustra does not seek nirvāṇa, but an affirmed Earth.

• Gnosticism: The perfected human (anthrōpos teleios) realizes inner divinity through knowledge and self-revelation.

▸ §4 – The “Last Man”: Satire of Modernity

Text: „Was ist Liebe? Was ist Schöpfung? Was ist Sehnsucht? Was ist Stern?“

Translation: “What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is a star?”

Philological Analysis:

• These rhetorical questions symbolize the loss of transcendence. The “last man” no longer questions, for he no longer desires.

• Niemand lacht mehr, auch nicht mehr klagt er.: “No one laughs anymore, nor do they complain.” The tone is prophetic parody—an “anti-apocalypse.”

Comparisons:

• Dostoevsky: The Underground Man anticipates this figure—resigned, ironic, pathologically self-referential.

• Marcuse / Huxley / Orwell: Nietzsche prefigures analyses of the subject numbed by technological comfort and the disappearance of tragic tension.

• Buddhism: By contrast, Buddhist detachment is not denial of passion but purification of illusory desire. The “last man” has amputated even that.

▸ §5 – The Laughter of the Sage

Text: „Ein Weiser war’s, dem sie zuriefen: „Jetzt will ich tanzen!“

Translation: “It was a wise man to whom they cried: ‘Now I want to dance!’”

Philological Analysis:

• Nietzschean laughter is not mockery, but ontological act: tragic laughter, Dionysian laughter. It affirms existence in the face of the abyss.

• tanzen (“to dance”): a key Nietzschean symbol. To dance is to be light amid the weight of the world.

Comparisons:

• Dionysus: God of theater, wine, and dance—in Nietzsche, the reversal of Christian solemnity.

• Sufism: The whirling dervish dances as prayer—spinning replicates the cosmic motion within the body.

• Zhuangzi: The sage who laughs upon hearing that life must be taken seriously—laughter as recognition of the emptiness of human constructs.

Conclusion. This philological and comparative analysis reveals that the Prologue to Thus Spoke Zarathustra is not merely a poetic preface, but a densely structured, symbolically saturated text that serves as a distorting mirror of multiple traditions—Platonism, Christianity, Eastern mysticism, Gnosticism, modern philosophy. Each line contains a critique of dominant values, a semantic inversion, and a proposal for a dancing, creative life without absolutes.

Nietzsche uses language as a symbolic alchemist: dissolving old words until, in their ruins, a new mode of existence begins to shine.

Español

Análisis filosófico académico del prólogo de Así habló Zaratustra de Friedrich Nietzsche

Autor: Prof. Eng. Carlos Serna II, PE MS LSSBB

Introducción

El Prólogo de Así habló Zaratustra (1883), escrito por Friedrich Nietzsche, es una pieza fundacional dentro del pensamiento nietzscheano, que condensa en clave poética, simbólica y filosófica muchas de las ideas centrales de su obra. Este texto, que funge como umbral al corpus aforístico y narrativo del libro, no sólo introduce al personaje de Zaratustra —figura alegórica inspirada en el profeta persa Zoroastro—, sino que también articula una crítica radical a la cultura occidental, una genealogía del espíritu humano y una propuesta de transvaloración moral que culmina en la noción del Übermensch (superhombre o suprahumano).

El presente análisis examina el Prólogo desde una perspectiva filosófica rigurosa, explorando sus dimensiones ontológicas, antropológicas, morales y metafísicas, al tiempo que lo sitúa en el marco más amplio del pensamiento moderno y postmetafísico.

1. El retiro y el regreso: la estructura arquetípica del camino del sabio. Zaratustra desciende de la montaña tras diez años de soledad: este gesto configura simbólicamente el retiro ascético del sabio, seguido por su decisión de compartir la sabiduría alcanzada. El esquema recuerda la figura del filósofo-rey de Platón y del profeta bíblico, pero Nietzsche subvierte su contenido. Zaratustra no desciende con verdades eternas, sino con una crítica incendiaria de los valores establecidos, proclamando la muerte de Dios y la necesidad de un nuevo horizonte de sentido.

Este ciclo de retirada y retorno expresa una tensión esencial entre la soledad creadora y la comunicación transformadora. Zaratustra es, como Nietzsche mismo, un espíritu trágico que ha roto con la moral del rebaño y pretende crear nuevos valores desde la experiencia del nihilismo superado.

2. La muerte de Dios y el ocaso de los valores absolutos. Uno de los pasajes más célebres del prólogo declara que “Dios ha muerto”. Aunque esta idea ya había sido expuesta en La gaya ciencia, en Zaratustra aparece no como un anuncio racional, sino como un acontecimiento mítico-existencial. No se trata simplemente de negar la existencia de un ser supremo, sino de anunciar el colapso de toda la estructura metafísica que sostenía los valores trascendentes de Occidente: la verdad absoluta, la moral universal, el alma inmortal, la historia providencial.

La muerte de Dios implica una crisis de sentido que inaugura el nihilismo. Sin embargo, Nietzsche no se detiene en esta constatación, sino que exige una superación del nihilismo, es decir, una creación activa de nuevos valores que no dependan de un fundamento externo al mundo, sino de la afirmación de la vida misma.

3. El Übermensch como ideal posthumano y figura del devenir. La idea del Übermenschaparece en el Prólogo como una respuesta afirmativa al nihilismo. El ser humano, dice Zaratustra, es “una cuerda tendida entre el animal y el superhombre”, un puente y no una finalidad. Esta visión antropológica dinamiza la concepción del ser humano, ya no como una esencia dada ni como un sujeto racional autosuficiente (como en Descartes o Kant), sino como un tránsito, un devenir creador, una posibilidad abierta.

El Übermensch no debe interpretarse como una criatura biológicamente superior, sino como una figura simbólica de aquel que ha trascendido la moral tradicional (especialmente la moral cristiana del resentimiento) y afirma la vida en todas sus dimensiones, incluso en su dolor, su caos y su devenir. Es, en este sentido, un “nuevo legislador”, un poeta de valores que no teme al abismo del sinsentido porque ha aprendido a bailar sobre él.

4. El desprecio al “último hombre”: crítica a la modernidad y al hedonismo burgués. Una figura fundamental del Prólogo es el “último hombre”, símbolo de la decadencia espiritual moderna. Este hombre satisfecho, cómodo, sin pasiones ni aspiraciones trascendentes, encarna para Nietzsche la negación de la vida elevada. Vive sin riesgos, sin profundidad, sin voluntad de poder. Rechaza el sufrimiento, pero también la grandeza.

El “último hombre” representa la culminación del proceso de igualación, domesticación y mediocridad impulsado por la modernidad liberal y la moral judeocristiana. En lugar del héroe trágico o del creador dionisíaco, el mundo moderno produce sujetos anestesiados, amantes del confort y enemigos de la diferencia. La crítica nietzscheana aquí coincide, en espíritu, con las posteriores diagnósticos de la sociedad tecnificada de Heidegger, la cultura de masas de Ortega y Gasset, o el hombre unidimensional de Marcuse.

5. El símbolo del sol: la voluntad de dar y la afirmación dionisíaca. El sol es el símbolo central del discurso de Zaratustra. Su luz no domina ni impone, sino que da. Al igual que el sabio, el sol se eleva para irradiar, no por necesidad, sino por superabundancia. Este símbolo recoge el núcleo de la ética afirmativa nietzscheana: el valor supremo no es el deber, el sacrificio o la redención, sino el derroche vital del que da sin esperar, del que crea sin pedir permiso.

En esta imagen, Nietzsche recupera lo dionisíaco como clave ontológica: el mundo es creación, devenir, exceso. El sabio verdadero no es quien escapa del mundo para buscar otra realidad (como en el platonismo o el cristianismo), sino quien dice “sí” al flujo cambiante de la existencia, a la risa, al dolor, al azar.

Conclusión. El Prólogo de Así habló Zaratustra es un manifiesto filosófico-poético que inaugura una nueva manera de pensar: no ya como sistema cerrado, sino como experiencia estética, transvaloradora y performativa. En su estructura dramática y simbólica se condensan las intuiciones más radicales de Nietzsche: la muerte de Dios, la crítica al nihilismo, la voluntad de poder, la necesidad de crear nuevos valores, y la figura del Übermensch como horizonte de una humanidad por venir.

Lejos de ofrecer certezas, el Prólogo invita a un viaje interior y colectivo, donde la filosofía no es contemplación, sino transformación. En Zaratustra, Nietzsche no busca transmitir una doctrina, sino provocar un temblor: una metamorfosis del alma que nos impulse a ser más de lo que somos.

Bibliografía académica

• Nietzsche, F. (2003). Así habló Zaratustra (trad. A. Sánchez Pascual). Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

• Heidegger, M. (1991). Nietzsche (Vol. I y II). Madrid: Trotta.

• Deleuze, G. (1962). Nietzsche et la philosophie. Paris: PUF.

• Löwith, K. (1997). De Hegel a Nietzsche: la quiebra revolucionaria del pensamiento en el siglo XIX. Madrid: Katz.

• Safranski, R. (2003). Nietzsche: Biografía de su pensamiento. Barcelona: Tusquets.

• Bataille, G. (1994). El culpable. Barcelona: Anagrama.

A continuación, desarrollaremos un análisis filológico y comparativo, sección por sección, del Prólogo de Así habló Zaratustra de Friedrich Nietzsche, atendiendo tanto al original alemán como a su traducción filosófica, simbólica y espiritual. Este enfoque nos permitirá rastrear con precisión los matices lingüísticos, las resonancias culturales y las relaciones intertextuales con otras tradiciones filosóficas y espirituales (griega, cristiana, mística oriental, etc.).

✦ Análisis filológico y comparativo del Prólogo de Así habló Zaratustra

▸ §1 – La salida de Zaratustra: el arquetipo del sabio solar.

Texto (alemán): „Als Zarathustra dreißig Jahre alt war, verließ er seine Heimat und den See seiner Heimat und ging in das Gebirge.“

Traducción: “Cuando Zaratustra tenía treinta años, abandonó su patria y el lago de su patria y se fue a la montaña.”

Análisis filológico:

• verließ (abandonó): verbo fuerte que implica ruptura radical, no sólo geográfica, sino espiritual. Connota una renuncia nietzscheana a la “patria” entendida también como tradición cultural, moral, lingüística.

• das Gebirge: no es simplemente “la montaña”, sino “la cordillera” o “el mundo montañoso”, símbolo recurrente de elevación espiritual y soledad filosófica.

Comparaciones:

• Platón: El ascenso al mundo inteligible en la Alegoría de la Caverna (República, VII) comparte la misma imagen de la elevación, pero Nietzsche revierte el vector: Zaratustra no sube para abstraerse del mundo sensible, sino para luego volver y transformar el mundo concreto.

• Evangelios: Jesús también se retira al desierto o a la montaña antes de comenzar su ministerio público. En ambos casos, la soledad precede la revelación.

• Mística oriental: Se asemeja al retiro de los rishis en los bosques védicos, o al ermitaño taoísta que retorna cuando la sabiduría ya no necesita del lenguaje.

▸ §2 – La maduración interior: “Yo amo a quien…”

Texto: „Zarathustra ward müde der Einsamkeit…“

“Zaratustra se cansó de la soledad…”

Análisis filológico:

• ward müde (se cansó): no expresa una simple fatiga física, sino una maduración espiritual. El verbo werden marca una transformación ontológica. Zaratustra deviene en alguien que debe dar.

• die Sonne hatte ihn gelehrt: “el sol le había enseñado”, metáfora potente: la luz como sabiduría que no se acumula, sino que se irradia.

Comparaciones:

• Heráclito: el logos como fuego que se propaga, no como doctrina fija.

• Evangelio de Juan: “La luz verdadera, que ilumina a todo hombre, venía al mundo” (Jn 1:9), aquí reinterpretada como afirmación vital, no como redención.

• Bhagavad Gītā: Krishna enseña que el sabio no busca ya resultados para sí, sino que actúa como ofrenda (karma yoga).

▸ §3 – El anuncio del Übermensch

Texto: „Ich lehre euch den Übermenschen.“

“Yo os enseño al superhombre.”

Análisis filológico:

• Übermensch: literalmente “el hombre que está más allá”, no “el hombre superior”. El prefijo über- denota trascendencia, pero también puede leerse como superación interna (Selbstüberwindung).

• Ich lehre euch: fórmula de autoridad profética, pero distorsionada. No es Moisés con las tablas, sino un nuevo profeta sin Dios.

Comparaciones:

• Heidegger: considera que el Übermensch aún permanece dentro de la metafísica occidental, como inversión de valores, y por ello lo critica en favor del ser.

• Buda Gautama: el ideal del arhat también es alguien que ha trascendido los condicionamientos humanos. Sin embargo, Zaratustra no busca el nirvana, sino la tierra afirmada.

• Gnosticismo: El hombre pleno (anthrōpos teleios) como quien realiza su divinidad interior a través del conocimiento y el autoconocimiento.

▸ §4 – El “último hombre”: sátira de la modernidad

Texto: „Was ist Liebe? Was ist Schöpfung? Was ist Sehnsucht? Was ist Stern?“

“¿Qué es el amor? ¿Qué es la creación? ¿Qué es el anhelo? ¿Qué es una estrella?”

Análisis filológico:

• Estas preguntas retóricas simbolizan la pérdida de toda trascendencia. El “último hombre” ya no pregunta porque no desea.

• Niemand lacht mehr, auch nicht mehr klagt er.: “Nadie ríe ya, tampoco se queja.” El tono es de parodia profética, como una “antiapocalipsis”.

Comparaciones:

• Dostoievski: El “hombre subterráneo” anticipa esta figura: resignado, irónico, patológicamente autorreferente.

• Marcuse / Huxley / Orwell: La crítica de Nietzsche prefigura los análisis del sujeto anestesiado por el confort tecnológico y la desaparición de la tensión trágica.

• Buda: Inversamente, el desapego en el budismo no es negación de la pasión, sino purificación del deseo ilusorio. El “último hombre” ha extirpado incluso eso.

▸ §5 – La risa del sabio

Texto: „Ein Weiser war’s, dem sie zuriefen: „Jetzt will ich tanzen!“

“Era un sabio a quien gritaban: ‘¡Ahora quiero bailar!’”

Análisis filológico:

• La risa nietzscheana no es burla, sino acto ontológico: risa trágica, risa dionisíaca. Es el acto afirmativo frente al abismo.

• tanzen (bailar): símbolo clave en Nietzsche. Bailar es ser ligero ante el peso del mundo.

Comparaciones:

• Dionisos: El dios del teatro, del vino, de la danza. En Nietzsche, es el reverso de la seriedad cristiana.

• Sufismo: El derviche giróvago baila como forma de oración: girar es repetir el movimiento del cosmos en el cuerpo.

• Zhuangzi: El sabio que ríe al escuchar que la vida es algo serio; la risa es reconocimiento de la vacuidad de las construcciones humanas.

Conclusión. Este análisis filológico y comparativo revela que el Prólogo de Así habló Zaratustra no es un simple anuncio poético, sino un texto densamente estructurado, simbólicamente saturado, que funciona como un espejo deformante de múltiples tradiciones: el platonismo, el cristianismo, la mística oriental, el gnosticismo, la filosofía moderna. Cada línea encierra una crítica a los valores dominantes, una inversión semántica y una propuesta de vida danzante, creadora y sin absolutos.

Nietzsche juega con el lenguaje como un alquimista simbólico: disuelve las viejas palabras hasta que resplandezca, en sus ruinas, una nueva forma de existencia.